Look around and imagine all the wireless (or even Ethernet) connectivity you rely on daily is gone. Computer labs are isolated to desktop applications and keyboarding practice since no websites will load. Office staff are unable to enter attendance, look up students, or pull reports from your information systems.

Imagine teachers losing five to ten minutes of class time or prep time because gradebooks and seating charts are just chugging along. Consider how far the digital literacy gap widens when students feel like they can't rely on the Internet as a valuable resource, so they abandon the attempt altogether. These kids will soon be competing for the same postsecondary opportunities as their broadband-connected peers in an increasingly tech-centered economy.

The more remote the school, the less likely it is to have access to high-speed fiber-optic connections. Without fiber, students are all but cut off from the one of the greatest resources available for learning—high-speed Internet.

Looking back at education decades ago, it might be tempting to shake this off as no big loss. After all, when students have a teacher and access to books, learning can still take place, right? Not exactly. Even basic digital learning tools including smartboards, student computer labs, and staff computers for recordkeeping require Wi-Fi connectivity to function.

More proof it’s not a choice: High-stakes state summative exams are now online and feature “technology enhanced items,” some of which include videos. If one of those videos takes 10 minutes to load or fails altogether, students are unable to complete the question. At the very least, this brings down scores and leads to questions about reliability and validity of these tests—questions that wouldn’t exist if each school had reliable, sufficient connectivity to high-speed Internet.

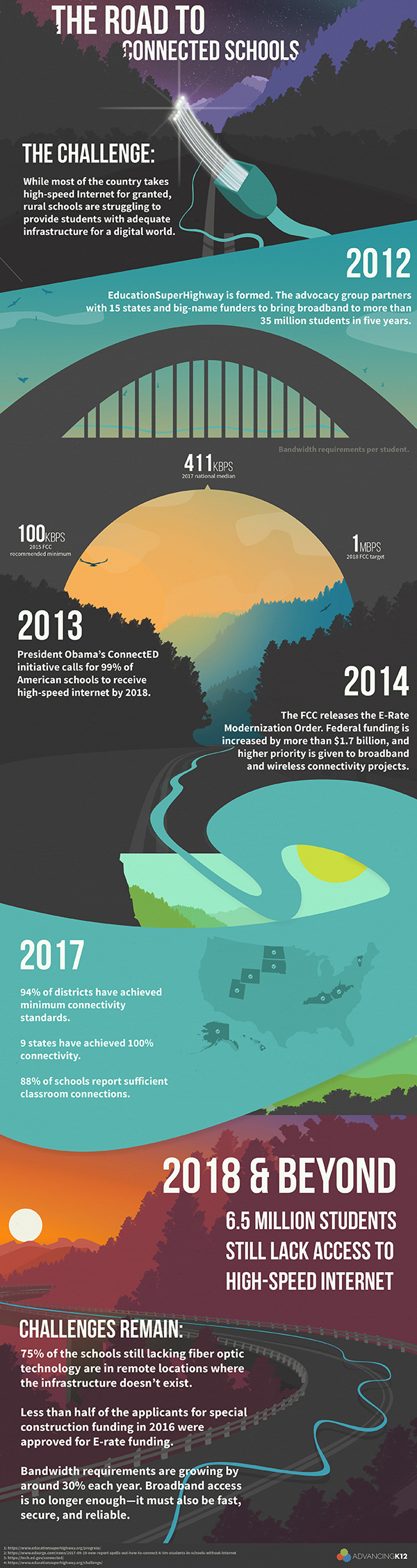

The Road to Connected Schools

In 2012, educators, lawmakers, and edtech leaders began working to close this gap in connectivity by forming the advocacy group EducationSuperHighway. They identified a need for upgraded fiber-optic connection in 63% of the nation’s schools. President Barack Obama subsequently introduced the ConnectED program, charging the Federal Communication Commission (FCC) with the goal of connecting 99% of American students to high-speed broadband Internet using E-rate funds.Beginning with $10 million raised through partnership with the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and other funders, EducationSuperHighway worked to partner with the 15 states in need of intervention to connect their students. In five years, they made steady progress:

- 94% of districts have achieved the 2015 minimum connectivity standards set by the FCC of 100 kilobits per second (kbps) per student.

- 88% of these schools say their classroom connection is sufficient for their needs.

- More than 35 million K-12 students have gained access to school Internet, including five million within the past year alone.

- Nine states have achieved 100% connectivity.

The Schools Less Traveled

Unfortunately, in some areas, it isn’t as simple as installing a few extra routers and flipping a couple switches. 75% of the schools lacking the fiber-optic technology required to deliver high-speed Internet are in remote locations where the infrastructure simply doesn’t yet exist. These schools must invest in significant construction for broadband even to be an option, a provision covered under the E-rate requests for funding.In 2014, the FCC modernized the E-rate program, increasing funding from $2.25 billion to $3.9 billion and shifting the focus from traditional telecommunication technology (think telephones and pagers) toward broadband and wireless, increasing the options, subsidies, and incentives for schools looking to invest in broadband connectivity. This modernization unfortunately did not minimize the red tape involved in applying for funds.

When an application for special construction funds is submitted to the E-rate program, it’s processed by the Universal Service Administrative Company (USAC), an organization tasked with providing nationwide access to high-speed internet for schools, libraries, and rural medical care. USAC acts according to FCC policy and submits requests for funding quarterly to the FCC. In 2017, leadership changed in the FCC under a new administration.

Rather than “pouring money into a broken system,” new FCC leader Ajit Pai has challenged USAC to streamline and simplify the application process, the bureaucracy of which compelled him to vote against modernizing E-rate in 2014. He urged the organization to complete the online portal originally set to launch in 2016 and blamed its lack of functionality for the increase in the backlog of applications. But problems persist. Of the 426 applicants for special construction funding in 2016, less than half were approved by USAC, and a lack of transparency has made it difficult for unfunded districts to get much in the way of clarification, especially when they have followed procedure and meet all the stated qualifications for funding. Of 2017’s 401 special construction applications, 94% were still pending as of September.

States are still not giving up on doing what they can to fill connectivity gaps in conjunction with the federal government—for example, Governor Susana Martinez of New Mexico earmarked millions of state dollars intended to match federal funds expected to be approved for special construction to connect 13 remote districts.

Upping the Speed Limit

In the meantime, as districts wait while funds are tied up, what does Internet access look like in under-connected schools?Old copper wire delivers a puny 1.5 megabits per second (mbps) to schools like Mississippi’s Vardaman High School, which need more than 20 times that bandwidth to meet even the minimum FCC recommendation of 100 kbps per student in the building. Worse, 85% of the largest districts in the nation are buying much more bandwidth in order to facilitate 1:1 and BYOD programs—the median bandwidth schools offer is hovering around 411 kbps per student, and it's growing by about 30% per year.

6.5 million students are missing out on the fundamental development of skills they need to be competitive and succeed in college and career. Groups like EducationSuperHighway are working diligently to fill the gaps. Will every American school have access to high-speed Internet? Probably. Can it come soon enough? The answer is unequivocally no.

See the vision for the future (and some of the roads yet untravelled) here:

WHAT'S NEXT FOR YOUR EDTECH? The right combo of tools & support retains staff and serves students better. We'd love to help. Visit skyward.com/get-started to learn more.

|

Erin Werra Blogger, Researcher, and Edvocate |

Erin Werra is a content writer and strategist at Skyward’s Advancing K12 blog. Her writing about K12 edtech, data, security, social-emotional learning, and leadership has appeared in THE Journal, District Administration, eSchool News, and more. She enjoys puzzling over details to make K12 edtech info accessible for all. Outside of edtech, she’s waxing poetic about motherhood, personality traits, and self-growth.