In 2006, one of the most comprehensive studies of educational leadership ever published uncovered a common leadership theme among thriving districts. Now, more than a decade leader, its findings still haven't received anywhere near the attention they deserve.

That comprehensive paper published by J. Timothy Waters & Robert Marzano (for McREL); School District Leadership that Works: The Effect of Superintendent Leadership on Student Achievement, concluded that superintendents, district office staff, and board members who “do the ‘right work’ in the ‘right way’” can and do contribute to student success—an assertion that not only contradicted popular criticism, but still rings true to me based on my own experiences and conversations with district leadership teams.

In the years since School District Leadership was published, we’ve seen technology, accountability measures, and regulatory demands grow at exponential rates. Many of the district leaders I know have had to create new administrative positions during this time period, while spreading additional responsibilities among existing staff and rewriting job descriptions on the fly.

In the face of so much change, I found myself revisiting a “surprising & perplexing” finding from the McREL study; that is, the concept of “defined autonomy” as a recurring trait among high performing leadership teams. It’s a management approach that I am personally invested in and one that seems to be at the heart of some of the most effective school districts I've had the pleasure of working with.

What does “defined autonomy” mean?

Defined autonomy is not a new leadership concept. In basic terms, it’s about empowering the leaders who report to you to take ownership of their department/school/project and use their own judgment to follow through on the vision and goals you have laid out for them.For the purpose of the aforementioned study, the alternative to defined autonomy was site-based management, a leadership style in which a superintendent would play an active role in the day-to-day operations of each individual school. The problem with this approach is that it turns superintendents into managers, rather than leaders. Building administrators no longer feel empowered and educators have a hard time distinguishing whom they’re supposed to be listening to.

This micromanaged environment is not a pleasant one to work in. It’s also not conducive to growth or innovation. Defined autonomy is not necessarily a “hands-off” leadership strategy, but it does represent a more productive way for leaders to use those hands (and minds).

What does it look like?

In a defined autonomy leadership model, organizational leaders serve as strategic visionary, cultural tone-setter, and coach. One of the hallmarks of this approach is a pervasive sense of accountability throughout the organization. Leaders are clear in their expectations, and they hold their team to a high standard in exchange for the freedom that comes with autonomy.In a school district, defined autonomy requires close collaboration between the superintendent and principals. It is the superintendent’s role to set firm objectives and provide principals with the right resources to support the vision. The latter can be a sticking point for some, but it’s easily overcome by bringing the technology department into the conversation.

It’s all well and good to say “we’re going to give students more control over their learning experience by switching to positive attendance,” or “we’re going to communicate better with parents to boost our attendance numbers,” but if the district’s practices and technology don’t support these efforts, principals are going to have a hard time getting their teachers to buy in to the vision.

The leader-as-mentor aspect of defined autonomy is perhaps the most crucial element of sustained success. You can empower your staff as much as you want, but if you’re not helping them grow as leaders, you’re liable to end up with inconsistent results from school to school. Hold regular meetings with your leadership team, maintain fair and equal measures of performance, and follow up on data with a focused professional development plan (which, not surprisingly, was another common theme among successful districts in School District Leadership).

How has it changed?

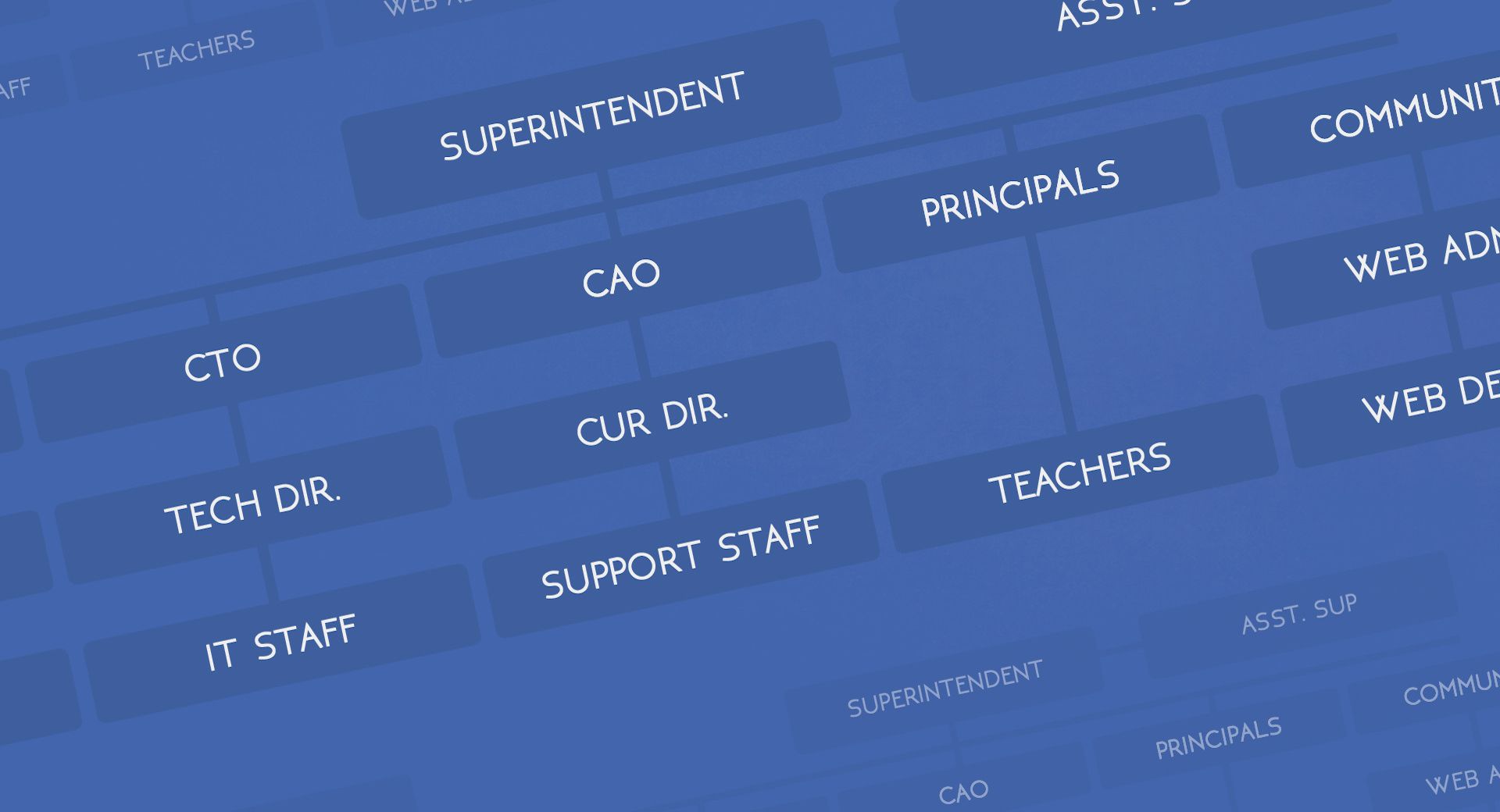

As administrative teams have grown larger to keep up with new demands and technologies, leadership responsibilities within the district office have shifted. Many superintendents now rely not just on their principals, but also on a number of C-level executives to drive core functions of district operations. Chief Academic Officers, Chief Technology Officers, and Chief Financial Officers are just the tip of the iceberg.Defined autonomy is not just for principals anymore. When I look at the K-12 landscape today, the executive leadership is spread thinner than ever before, necessitating a shift toward autonomy and away from day-to-day management.

Our CEO, Cliff King, recently published his thoughts on the changing role of executive leadership. In his article, he drew some parallels between the challenges faced by private sector CEOs and superintendents. In his words; “CEOs can no longer run even a small organization on their own…it is all but impossible to play a significant role in every aspect of day-to-day operations.”

The majority of the administrators I’ve worked with in high achieving districts are bringing their diverse areas of expertise to the table without fear of micromanagement. Far from resembling a “blob,” these key personnel are leading by example and driving academic success.

By entrusting all leaders to use their own judgment to run their respective schools and departments, superintendents can focus on spearheading the culture and mission of the school district. The result is a district where leaders are allowed to lead and staff development at all levels is a top priority. That sure sounds like a recipe for student success.

WHAT'S NEXT FOR YOUR EDTECH? The right combo of tools & support retains staff and serves students better. We'd love to help. Visit skyward.com/get-started to learn more.

|

Ray Ackerlund President |